去看看

去看看

《2017 美国成人高血压预防、检测、评估及管理指南》于 2017 年 11 月 13 日在美国心脏协会(American Heart Association,AHA)科学年会上正式发布(以下简称 2017 版指南)[1]。与上一版指南相比,2017 版指南的变动较大。本文就该指南内容进行摘译。

2017 版指南采用 2015 年 8 月更新的推荐等级(class of recommendation,COR)和证据水平(level of evidence,LOE)定义 [2-4](表 1)。

2017 版指南是对第 7 届美国预防、检测、评估及治疗高血压委员会(JNC 7)指南的更新 [5],纳入了许多新的信息,包括基于诊室血压的相关心血管疾病(cardiovascular disease,CVD)危险因素、动态血压监测(ambulatory blood pressure monitoring,ABPM)、家庭血压监测(home blood pressure monitoring,HBPM)、远程医疗及其他领域的相关研究结果。

1 血压与心血管疾病危险因素

1.1 相关性

观察性研究已证实,收缩压(systolic blood pressure,SBP)和舒张压(diastolic blood pressure,DBP)的升高与 CVD 风险的增加密切相关 [6,7]。对 61 项前瞻性研究的荟萃分析显示,SBP 从< 115 mmHg 至> 180 mmHg、DBP 从< 75 mmHg 至> 105 mmHg,CVD 风险以对数线性方式逐渐增加。SBP 每增加 20 mmHg,DBP 每增加 10 mmHg,患者因脑卒中、心脏病或其他血管性疾病死亡的风险加倍 [6]。在另一项超过 100 万例年龄≥ 30 岁成年患者的研究中,SBP 和 DBP 升高分别与 CVD 事件、心绞痛、心肌梗死、心力衰竭、脑卒中、外周动脉疾病(peripheral artery disease, PAD)及腹主动脉瘤的风险增加有关 [7]。在 30 岁至> 80 岁的年龄范围,CVD 风险的增加与 SBP 和 DBP 升高之间的相关性已有报道。

1.2 人群风险

在 2010 年,高血压是全球死亡和伤残调整生命年(disability-adjusted life years, DALY)的主要原因 [8,9]。在美国,与其他任一可改变的 CVD 危险因素相比,高血压导致了更多的 CVD 死亡,是仅次于吸烟的一种可预防的死亡原因。对 23 272 例美国国家健康与营养调查(NHANES)人群的随访研究显示,超过 50% 的死于冠心病和卒中的患者合并高血压 [10]。基于群体的社区动脉粥样硬化风险(ARIC)研究显示,25% 的心血管事件与高血压相关 [11]。在北曼哈顿研究中,与高血压相关的事件发生率,女性高于男性(32% ︰ 19%),黑人高于白人(36% ︰ 21%)[12]。2012 年,在美国,高血压是继糖尿病之后导致终末期肾病(endstage renal disease,ESRD)的第二主因,与 34% 的ESRD 相关 [13]。

1.3 高血压与相关慢性情况并存

许多成人高血压患者常合并其他CVD危险因素(表2)。

推荐依据:观察性研究已证实,CVD危险因素常合并存在,17%的患者中常合并存在≥3个危险因素。对257 384例患者18项队列研究的荟萃分析结果证实,存在≥2个CVD危险因素患者的CVD死亡、非致死性心肌梗死、致死性或非致死性脑卒中的罹患风险高于仅有1个危险因素的患者。

2 血压的分级

2.1 高血压的定义

尽管高血压与 CVD 风险增加之间存在连续性相关,但对血压水平进行分级有助于制订临床和公共健康决策。2017 版指南中,根据测得的平均血压将血压水平分为 4 级(表 3)。

推荐依据:观察性研究的荟萃分析已证实,升高的血压和高血压与 CVD、ESRD、亚临床动脉粥样硬化及全因死亡的风险增加有关 [7,14-18]。推荐的血压分级系统在未治疗的患者中作为一种决定预防或治疗高血压的辅助工具是最有价值的。 另外, 也可将其用于评估降压治疗是否成功。

2.2 高血压的流行病学

高血压分级的切点被用于确定诊断及人群研究, 而该切点的选择极大地影响了患病率的评估。 根据2017版指南中推荐的高血压定义及JNC 7中的高血压定义, 美国一般成年人(≥20岁) 中高血压患病率的评估结果见表4。

3 血压测量

3.1 准确的诊室血压测量

3.2 诊室外血压和自我血压监测

诊室外血压测量有助于高血压的确诊和管理。自我血压监测指一个人在家里或诊室外的其他地方进行规律的血压测量。诊室血压、家庭自测血压、日间血压、夜间血压及24小时动态血压中SBP/DBP相对应的数值见表5。

推荐依据:ABPM 常可用于获得超过 24 小时的诊室外血压数据。患者通过 HBPM 获得诊室外血压数据的记录。根据美国预防服务工作组完成的一项系统综述报告,在预测 CVD 的长期结局方面,ABPM 优于诊室血压。

3.3 隐匿性高血压和白大衣高血压

在未接受药物治疗患者中,白大衣高血压或隐匿性高血压的检测见图1、图2。

在已接受药物治疗患者中,白大衣效应或隐匿性未控制的高血压的检测见图3。

4 高血压的原因

遗传易感性 : 高血压是一种复杂的多基因病,多种基因或基因组合影响血压。

环境因素 : 超重和肥胖、 钠摄入、 钾、 体育健身、 酒精等均与高血压相关。

一般人群中, 随着年龄增加, 血压升高。 早产与成年期的SBP增加4 mmHg和DBP增加3 mmHg有关, 且在女性中更显著。 低出生体重也与后期较高的血压相关。

4.1 高血压的继发原因

继发性高血压的筛查见图4。

靶器官损害 : 如脑血管疾病、 高血压性视网膜病变、 左心室肥厚、 左心室功能异常、 心力衰竭、 冠心病、 慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease,CKD)、 蛋白尿、PAD。

继发性高血压的病因、 临床表现及诊断性筛查试验见表6。

罕见病因包括:嗜铬细胞瘤 / 副神经节瘤(0.1% ~ 0.6%)[29]、Cushing 综合征(< 0.1%)、甲状腺功能减退(<1%)、甲状腺功能亢进(<1%)、主动脉缩窄(未确诊的或修复的,0.1%)、原发性甲状旁腺功能亢进(罕见)、先天性肾上腺皮质增生症(罕见)、原发性醛固酮增多症以外的盐皮质激素过多综合征(罕见)、肢端肥大症(罕见)[30]。

4.2 原发性醛固酮增多症

原发性醛固酮增多症是导致继发性高血压的主要原因之一(可见于 5% ~ 10% 的高血压患者、 20% 的难治性高血压患者)。与原发性高血压相比,原发性醛固酮增多症中醛固酮的组织毒性作用会导致更严重的靶器官损害。

4.3 肾动脉狭窄

动脉粥样硬化(90%)是肾动脉狭窄最常见的原因,而非动脉粥样硬化性疾病(其中纤维肌性发育不良最常见)很少见,且易出现于较年轻和较健康的患者中。通过外科肾动脉重建缓解缺血以及缺血后的肾素释放是一种有创操作,术后患者死亡率高达 13%。数项研究结果提示,单独通过血管内操作恢复血流不优于药物治疗 [31,32]。

4.4 阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停

阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停(obstructive sleep apnea, OSA)在难治性高血压患者中的发病率很高(≥80%),推测持续气道正压通气(continuous positive airway pressure,CPAP)治疗可能对于难治性高血压具有更明显的降压作用 [33]。

但是,数项关于 CPAP 对血压影响的研究已证实,CPAP 仅具有轻度降压作用(2 ~ 3 mmHg),且依赖于患者使用 CPAP 的依从性、OSA 的严重程度以及是否存在日间嗜睡 [34]。一项良好设计的随机对照试验结果证实,在中重度 OSA 合并 CVD 患者中,与单独进行常规护理相比,CPAP 联合常规护理未能预防心血管事件 [35]。

5 非药物干预

非药物干预在降压方面是有效的,最重要的干预方式包括:减重、控制高血压膳食疗法(dietary approaches to stop hypertension,DASH)、限盐、增加钾摄入、增加体力活动、减少酒精消耗。

6 患者评估

6.1 实验室检查和其他诊断方法

新诊断的高血压患者均应进行实验室检查,以便获得 CVD 危险因素的特点、确定药物治疗的基线数据及筛查高血压的继发性原因(表 7)。

6.2 心血管靶器官损害

脉搏波传导速度、颈动脉内中膜厚度、冠状动脉钙化积分是血管靶器官损害和动脉粥样硬化的无创评估指标。

左心室肥厚是高血压的继发表现及未来心血管事件的独立预测因子,可通过心电图、超声心动图或磁共振进行检测。

7 高血压的药物治疗

启动降压治疗的推荐以及通过风险评估指导高血压的治疗。

血压阈值及治疗和随访建议见图 5。

7.1 药物治疗的一般原则

大量临床研究证实,降压药物不仅能够降低血压,而且能够减少 CVD 和脑血管事件,降低死亡风险。一线口服降压药物包括:噻嗪样和噻嗪型利尿剂、血管紧张素转化酶抑制剂(angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor,ACEI)、血管紧张素Ⅱ受体拮抗剂(angiotensin Ⅱ receptor blocker,ARB)、二氢吡啶类钙通道阻滞剂(calcium channel blocker, CCB)、非二氢吡啶类 CCB。二线口服降压药物包括:袢利尿剂、保钾利尿剂、醛固酮受体拮抗剂、心脏选择性 β 受体阻滞剂、具有血管扩张作用的心脏选择性 β 受体阻滞剂、非心脏选择性 β 受体阻滞剂、具有内在拟交感活性的 β 受体阻滞剂、α/β 受体阻滞剂、直接肾素抑制剂、α1 受体阻滞剂、中枢 α1 受体激动剂、其他中枢降压药及直接血管扩张剂。

7.2 高血压患者的目标血压

7.3 起始药物选择

7.4 起始单药治疗 VS 起始联合治疗的选择

8 高血压合并其他疾病

合并的疾病可能影响高血压治疗的临床决策,包括:缺血性心脏病、射血分数减低的心力衰竭、射血分数保留的心力衰竭、CKD(包括肾移植)、脑血管疾病、心房颤动、PAD、糖尿病和代谢综合征。

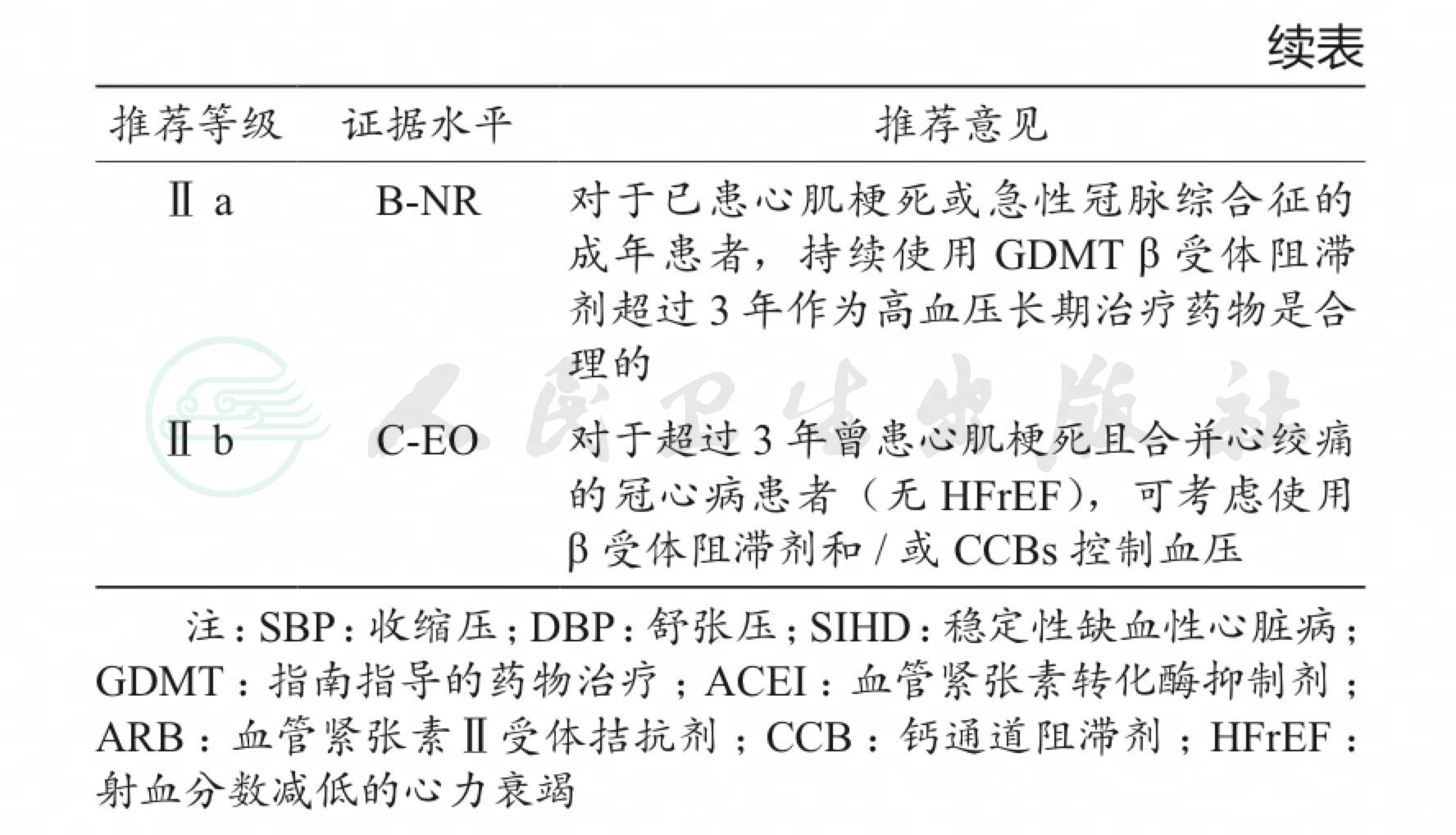

8.1 稳定性缺血性心脏病

高血压是缺血性心脏病的主要危险因素,大量随机对照试验已证实降压药物降低缺血性心脏病的临床获益。合并稳定性缺血性心脏病(stable ischemic heart disease,SIHD)患者的高血压管理见图 6。

8.2 心力衰竭

8.2.1 射血分数减低的心力衰竭

8.2.2 射血分数保留的心力衰竭

8.3 慢性肾脏病

合并CKD患者的高血压管理见图7。

肾移植后高血压:

肾移植后,由于既往存在肾脏病、免疫抑制剂作用、存在同种异体移植物病理,常出现高血压。移植受者常携带多种CVD危险因素,并具有发生心血管事件的高风险。

8.4 脑血管病

脑卒中是死亡、残疾及痴呆的首要原因[42]。脑卒中患者的血压管理是复杂的。

8.4.1 急性脑出血

自发性、非创伤性脑出血是全球发病和死亡的主要原因 [43]。血压升高在急性脑出血中非常多见,并与血肿扩大、神经功能恶化、脑出血后的依赖生存有关。急性脑出血患者的高血压管理见图 8。

8.4.2 急性缺血性脑卒中

8.4.3 卒中二级预防

在美国,每年有超过 750 000 例患者发生脑卒中,其中 25% 以上的患者是再发脑卒中 [43]。

8.5 外周动脉疾病

8.6 糖尿病

8.7 心房颤动

8.8 瓣膜性心脏病

8.9 主动脉疾病

9 特殊的患者人群

9.1 与性别相关的问题

< 50 岁女性的高血压发病率低于男性,≥50 岁女性则高于男性 [45]。妊娠期间的高血压治疗则有特殊推荐。

(1) 女性:目前,没有证据显示性别与药物疗效相关。而且,包括 100 000 例男性高血压患者和 90 000 例女性高血压患者的 31 项随机对照试验的大规模荟萃分析结果显示,男性和女性在 CVD 的结局方面不具有显著性差异。

在 TOMHS 研究中,女性患者使用降压药物的不良反应发生率是男性患者的 2 倍。ACEI 所致咳嗽和 CCB 相关水肿的发生率女性患者高于男性患者。女性患者使用利尿剂更易发生低钾血症和低钠血症,较少发生痛风。妊娠过程中的高血压亦有特殊性。

(2) 妊娠:

9.2 老年人

10 其他情况

10.1 难治性高血压

根据既往 140/90 mmHg 的切点,人群中难治性高血压的发病率约为 13%[47]。数项队列研究已提示, 常见的难治性高血压危险因素包括老年、肥胖、CKD、黑人及糖尿病。如以新推荐的< 130/80 mmHg 为血压控制目标,预计发病率约增加 4%。难治性高血压的评估包括患者特征、假性难治性(血压技术、白大衣高血压、药物依从性)以及筛查继发性高血压。

10.2 高血压危象——急症和亚急症

高血压危象的诊断和治疗见图 9。

10.3 患者接受外科手术

11 提高高血压治疗和控制的策略

11.1 降压药物的依从性

11.2 健康信息技术——提高高血压控制的重要策略

11.2.1 电子健康记录和患者登记

11.2.2 通过远程医疗提高高血压控制

12 血压阈值和药物治疗的血压目标

指南中推荐了一般和特殊合并症时的血压阈值和目标(表8)。

北京大学人民医院孙宁玲教授点评

《2017美国成人高血压预防、检测、评估及管理指南》由美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health,NIH)主导并委托美国心脏病学会/美国心脏协会(American College of Cardio logy/American Heart Association,ACC/AHA)制定,同时有9个美国相关的重要学会参加。由来自多个专业的21位成员组成指南写作委员会,历时3年,完成15个章节的高血压指南编写工作,与企业之间无利益关系。该指南依据了循证推荐作为临床应用的推荐(提出的每条建议均含有推荐等级和证据水平)。该指南为存在心血管疾病(cardiovascular disease,CVD)风险的患者提供了临床实践建议,具有一定的权威性。

1 美国2017年ACC/AHA指南所做的重要修订

(1)将高血压诊断标准由140/90下移至130/80 mmHg。

(2)将高血压患者的血压控制目标全部定在 <130/80 mmHg(包括>65岁患者)。

(3)高血压患者的治疗基于双重条件:即血压水平和10年动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病(atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,ASCVD)风险。当血压≥ 130/80 mmHg,如10年ASCVD风险<10%应采取以生活方式干预为主的治疗,只有当血压≥ 140/90 mmHg才可进行药物治疗;对血压≥ 130/80 mmHg,10年ASCVD风险>10%以及有心脑血管疾病的二级预防人群即可启动药物治疗。这种理念其实与我国的治疗策略是差不多的。

(4)血压的评估基于血压的监测方法和靶器官受损的程度:诊室外血压测量(动态血压监测、家庭血压监测)是推荐的,有利于白大衣高血压和隐匿性高血压的诊断。自动化诊室血压测量是临床鼓励采用的监测方法。在靶器官损害筛查中,对于心血管分层管理具有重要的意义和价值。

2 对美国2017年ACC/AHA指南的思考

美国指南的这种血压分级理念和治疗理念适合中国吗?应该说,管理和预防的理念是非常可取的。我们的诊断目标是否需要下移至130/80 mmHg,要看中国是否有相关随机对照试验的证据。现有流行病学研究显示,我国血压在120 mmHg以上的人群,临床CVD风险随着血压的升高而上升,如能管理好130/80 mmHg这部分人群的血压,将有利于减少高血压的发生,但是否可以减少心脑血管事件,目前仍需要不断积累证据。

美国指南对老年高血压患者(>65岁)的目标血压推荐为<130/80 mmHg,而JNC 8推荐的目标血压<150 mmHg。时隔3年血压下移了20 mmHg,这种落差令人诧异。仅依据SPRINT研究(尽管是生活状态良好的老年人)就积极进行了数值的改变,但SPRINT研究人群在随机对照试验中预先规定了很多条件。在真实世界中,老年人存在更多躯体和心理的复杂性,而这种“一刀切”的做法慎重程度欠佳,由此可能带来老年人发病风险的提高。在我国会更加谨慎地对待这部分老年人的血压管理。

3 美国2017年ACC/AHA高血压指南的启迪

(1)预防理念前移。

(2)血压的诊断应采用被认证的合格的血压测量设备和合适的血压测定方法。

(3)诊室血压应与家庭血压监测和动态血压监测相结合,以排除和鉴别白大衣高血压及隐匿性高血压。

(4)干预时机:应依据血压水平和10年CVD风险双重标准考虑药物治疗。

(5)干预治疗:生活方式干预仍是有效的降压方式。在药物联合治疗方案中,以不同机制药物的联合最佳,以血压水平决定选择自由联合或固定复方。

[1] Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA

Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines[J]. Hypertension, 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Methodology Manual and Policies From the ACCF/AHA Task Force on

Practice Guidelines. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, 2010[EB/OL]. http://assets. cardiosource.com/Methodology_Manual_for_ACC_AHA_Writing_Committees.pdfandhttp://professional.heart.org/idc/ groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/documents/downloadable/ ucm_319826.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2017.

[3] Halperin JL, Levine GN, Al-Khatib SM, et al. Further Evolution of the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendation Classification System: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines[J]. Circulation, 2016, 133(14):1426-1428.

[4] Jacobs AK, Kushner FG, Ettinger SM, et al. ACCF/AHA clinical practice guideline methodology summit report: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines[J]. Circulation, 2013, 127(2):268-310.

[5] Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure[J]. Hypertension, 2003, 42(6):1206-1252.

[6] Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a metaanalysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies[J]. Lancet, 2002, 360(9349):1903-1913.

[7] Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9932):1899-1911.

[8] Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9859):2224-2260.

[9] Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global Burden of Hypertension and Systolic Blood Pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mmHg, 1990-2015[J]. JAMA, 2017, 317(2):165-182.

[10] Ford ES. Trends in mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease among hypertensive and nonhypertensive adults in the United States[J]. Circulation, 2011, 123(16):1737-1744.

[11] Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal trends in the population attributable risk for cardiovascular disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study[J]. Circulation, 2014, 130(10):820-828.

[12] Willey JZ, Moon YP, Kahn E, et al. Population attributable risks of hypertension and diabetes for cardiovascular disease and stroke in the northern Manhattan study[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2014, 3(5):e001106.

[13] Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, et al. US Renal Data System 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2015, 66(1 Suppl 1):Svii, S1-S305.

[14] Guo X, Zhang X, Guo L, et al. Association between pre-hypertension and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2013, 15(6):703-716.

[15] Huang Y, Cai X, Li Y, et al. Prehypertension and the risk of stroke: a meta-analysis[J]. Neurology, 2014, 82(13):1153-1161.

[16] Huang Y, Cai X, Liu C, et al. Prehypertension and the risk of coronary heart disease in Asian and Western populations: a meta-analysis[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2015, 4(2):e001519.

[17] Huang Y, Cai X, Zhang J, et al. Prehypertension and incidence of ESRD: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2014, 63(1):76-83.

[18] Shen L, Ma H, Xiang MX, et al. Meta-analysis of cohort studies of baseline prehypertension and risk of coronary heart disease[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2013, 112(2):266-271.

[19] Uhlig K, Balk EM, Patel K, et al. Self-Measured Blood Pressure Monitoring: Comparative Effectiveness[M]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.S.), 2012.

[20] Margolis KL, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, et al. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control: a cluster randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(1):46-56.

[21] McManus RJ, Mant J, Haque MS, et al. Effect of self-monitoring and medication self-titration on systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: the TASMIN-SR randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2014, 312(8):799-808.

[22] Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2015, 163(10):778-786.

[23] Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2015, 162(3):192-204.

[24] Asayama K, Thijs L, Li Y, et al. Setting thresholds to varying blood pressure monitoring intervals differentially affects risk estimates associated with white-coat and masked hypertension in the population[J]. Hypertension, 2014, 64(5):935-942.

[25] Mancia G, Bombelli M, Brambilla G, et al. Long-term prognostic value of white coat hypertension: an insight from diagnostic use of both ambulatory and home blood pressure measurements[J]. Hypertension, 2013, 62(1):168-174.

[26] Viera AJ, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, et al. Reproducibility of masked hypertension among adults 30 years or older[J]. Blood Press Monit, 2014, 19(4):208-215.

[27] Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, et al. Prognosis of whitecoat and masked hypertension: International Database of Home blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome[J]. Hypertension, 2014, 63(4):675-682.

[28] Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 101(5):1889-1916.

[29] Lenders JWM, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochr omocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99(6):1915-1942.

[30] Katznelson L, Laws ER Jr, Melmed S, et al. Acromegaly: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99(11):3933-3951.

[31] Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(1):13-22.

[32] Riaz IB, Husnain M, Riaz H, et al. Meta-analysis of revascularization versus medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2014, 114(7):1116-1123.

[33] Parati G, Lombardi C, Hedner J, et al. Position paper on the management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: joint recommendations by the European Society of Hypertension, by the European Respiratory Society and by the members of European COST (COoperation in Scientific and Technological research) ACTION B26 on obstructive sleep apnea[J]. J Hypertens, 2012, 30(4):633-646.

[34] Muxfeldt ES, Margallo V, Costa LMS, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on clinic and ambulatory blood pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Hypertension[J]. Hypertension, 2015, 65(4):736-742.

[35] McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(10):919-931.

[36] Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10022):957-967.

[37] Sundstrom J, Arima H, Woodward M, et al. Blood pressurelowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analy sis of individual patient data[J]. Lancet, 2014, 384(9943):591-598.

[38] Sundstrom J, Arima H, Jackson R, et al. Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2015, 162(3):184-191.

[39] Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pres sure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10017): 435-443.

[40] SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(22):2103-2116.

[41] Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Cardiol, 2017, 2(7):775-781.

[42] Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, Barsan WG, et al. Intensive BloodPressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(11):1033-1043.

[43] Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2017 update: A Report From the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2017, 135(10):e146-e603.

[44] Zhao D, Wang ZM, Wang LS. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on essential hypertensive patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. J Biomed Res, 2015, 29(6):475-485.

[45] Pucci M, Sarween N, Knox E, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in women of childbearing age: risks versus benefits[J]. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol, 2015, 8(2):221-231.

[46] Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(24):2673-2682.

[47] Achelrod D, Wenzel U, Frey S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of resistant hypertension in treated hype rtensive populations[J]. Am J Hypertens, 2015, 28(3):355-361.

[48] Andersson C, Merie C, Jorgensen M, et al. Association of β-blocker therapy with risks of adverse cardiovascular events and deaths in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery: a Danish nationwide cohort study[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2014, 174(3):336-344.

[49] Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatioN Prospective Cohort[J]. Anesthesiology, 2017, 126(1):16-27.

[50] Rakotz MK, Ewigman BG, Sarav M, et al. A technologybased quality innovation to identify undiagnosed hypertension among active primary care patients[J]. Ann Fam Med, 2014, 12(4):352-358.

[51] Borden WB, Maddox TM, Tang F, et al. Impact of the 2014 expert panel recommendations for management of high blood pressure on contemporary cardiovascular practice: insights from the NCDR PINNACLE registry[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014, 64(21):2196-2203.

[52] Burke LE, Ma J, Azar KM, et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2015, 132(12):1157-1213.